|

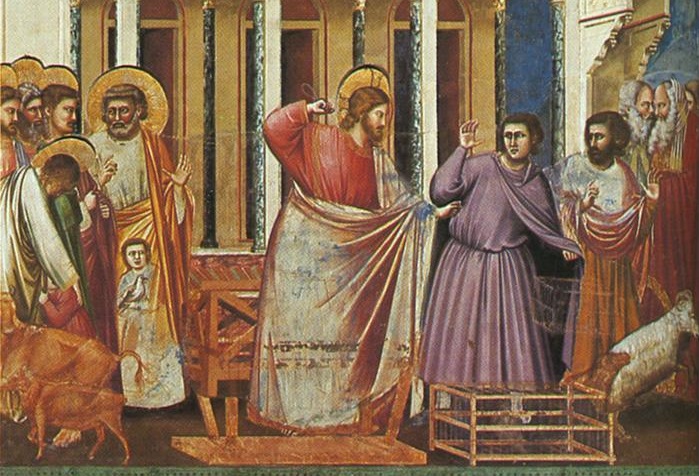

| Giotto, Casting Out the Money Changers |

There's glory for you!

-- Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass

I continue my notes on the Fourth Gospel, following for convenience the traditional practice of referring to it and its author as "John." The text is in purple; everything else is my notes.

*

The marriage in Cana

[1] And the third day there was a marriage in Cana of Galilee; and the mother of Jesus was there:

Different translations interpret "the third day" differently -- as "on Tuesday," "three days later," and "two days later." The last reading is the correct one. John 1 has already established the narrative pattern of saying "the next day," so the "on Tuesday" reading is extremely unlikely; and it is my understanding that for NT writers "on the third day" means what we would call two days later, the day from which we are counting being considered the first. (For example, Jesus died on Friday and rose "on the third day," on Sunday.)

Here's the chronology of events so far:

- Day 1: John meets with a delegation of priests and Levites and tells them he is not the Messiah.

- Day 2: John announces that he has seen the Spirit descend and abide on Jesus, and that Jesus is the Lamb of God.

- Day 3: John again hails Jesus as the Lamb of God, and Andrew and another disciple follow him. Later Simon Peter joins them.

- Day 4: Jesus plans to go to Galilee, and calls Philip to follow him there. They are joined by Nathanael. They must start their journey to Galilee on this day as well.

- Day 5: Nothing is reported. Presumably they spend the whole day en route to Galilee.

- Day 6: Jesus and his disciples attend the marriage in Cana.

The journey back to Galilee would have been about 90 miles, so covering it in two days would really be pushing it! An adult in good physical shape can cover 20 miles a day with normal breaks, or 30 miles under forced-march conditions. One rather imagines Jesus and his disciples going at a leisurely pace and conversing along the way; the idea of their covering 45 miles a day, as if they were Maasai warriors or something, stretches plausibility.

Perhaps we are to understand that they went to Galilee (spending an unspecified number of days on the road) and found Nathanael there, and then attended the wedding two days after meeting him. Or perhaps we shouldn't take this writer's "the next day" connectors too literally; perhaps he is simply stringing together several important scenes from Christ's ministry without being too exact about the timescale.

*

[2] And both Jesus was called, and his disciples, to the marriage.

It has been suggested that the marriage in Cana was Jesus' own wedding, but if so the fact has been deliberately disguised. The text we have portrays him as a guest, invited along with his mother and his disciples. There is no mention of Jesus' father, suggesting that he may already have died by this point.

*[3] And when they wanted wine, the mother of Jesus saith unto him, They have no wine. [4] Jesus saith unto her, Woman, what have I to do with thee? mine hour is not yet come. [5] His mother saith unto the servants, Whatsoever he saith unto you, do it.

This reads as if Jesus' mother were hosting the wedding party. She is in a position to give orders to the servants, and she says "They have no wine" -- not we -- suggesting that she is not just another of the wedding guests.

If Jesus' mother is indeed the hostess, why does the wedding take place in Cana rather than in Jesus' hometown of Nazareth? If I correct in inferring that Jesus' father had already died, it is possible that his mother either moved back to her parents' hometown or else remarried someone from Cana.

"Woman," I am told, is a normal and respectful form of address in this context, and some translations go with "dear lady" or something along those lines.

"What have I to do with thee?" is perhaps better translated as "What is that to you and me?" ("Τί ἐμοὶ καὶ σοί, " literally "What to-me and to-you") -- that is, "What concern is that of ours?" He is not asking the bizarre question of what he has to do with his own mother, as if he were disowning her, but rather what the two of them have to do with providing wine for the party. So perhaps his mother is not the hostess after all.

It certainly sounds as if Jesus is refusing to do anything about the wine problem, since it is not his concern and his time (to perform public miracles?) has not yet come. His mother, however, blithely ignores this refusal, proceeds just as if he had agreed to help, and tells the servants to do what he says! Say what you will about this, I think it's a pretty realistic portrayal of family dynamics -- which are apparently not so different even if your son happens to be the Son of God.

Jesus' mother seems to take it for granted that he will be able to conjure up some wine, so, despite the characterization of this episode as his "beginning of miracles," it is apparent that has already manifested paranormal abilities.

*

[6] And there were set there six waterpots of stone, after the manner of the purifying of the Jews, containing two or three firkins apiece. [7] Jesus saith unto them, Fill the waterpots with water. And they filled them up to the brim. [8] And he saith unto them, Draw out now, and bear unto the governor of the feast. And they bare it.

John Gill's Exposition of the Entire Bible explains, citing various ancient Jewish authorities:

At a wedding were set vessels of various sizes to wash hands and feet in; there was one vessel called משׁיכלא, which the gloss says was a large pitcher, or basin, out of which the whole company washed their hands and their feet; and there was another called משׁיכלתא , which was a lesser and beautiful basin, which was set alone for the more honourable persons, as for the bride, and for any gentlewoman; and such might be these six stone jars, or pots.

Although the KJV makes it sound as if each pot already contained two or three firkins of water, the word rendered "containing" is more correctly translated as "having space for"; we are being told the capacity of the pots, not their contents. (The word translated "firkin" most probably represents about nine gallons, though there is some uncertainty about this.)

If Gill is right, though, the pots did probably already have some water in them -- and not clean water, either, but the water in which all the wedding guests had washed their hands and feet! (The miracle takes place while the party is in progress; the guests would already have made their ablutions before entering.) Jesus has the servants top them up with water and then turns it into wine. The pots must be located outside the room where the party is taking place, which is why the governor of the feast has no knowledge of what Jesus has had the servants do.

*

[9] When the ruler of the feast had tasted the water that was made wine, and knew not whence it was: (but the servants which drew the water knew;) the governor of the feast called the bridegroom, [10] And saith unto him, Every man at the beginning doth set forth good wine; and when men have well drunk, then that which is worse: but thou hast kept the good wine until now.

It's hard not to see an element of comic irony in this, with the servants laughing up their sleeves and whispering, "They think this is fine wine. They don't realize it was actually made from their dirty bath water!" If the governor and the guests knew where the wine came from, they would likely be as much disgusted and offended as amazed. ("Moab is my washpot," says the Psalmist, clearly meaning by the expression to convey his utter contempt for that country.)

But the real joke here is that there's no joke. Jesus isn't tricking them into drinking filthy water. After he works his magic on it, it really is fine wine, and never mind what it was before. We might see this as a symbolic announcement of his intention to use publicans and sinners and other such riffraff as the raw materials from which to create saints and, ultimately, Gods.

Or perhaps the symbolism runs deeper. Washing one's hands and feet preparatory to participating in a wedding feast symbolizes repenting before entering the kingdom of God -- but even the dust and dirt that has been washed off is not discarded, but rather transformed into the wine for the feast. Vice and sin are not destroyed but transfigured, as in the C. S. Lewis story (I forget which) where a man crushes the reptile that represents his besetting sin, only to see it transform into a fine horse.

*

The Gospel gives no information as to how the miracle was carried out. We are not told when or how the water became wine, just that it had already become so by the time the governor tasted it. If Jesus said or did anything observable to effect the transformation, we are not told of it. The pivotal event, the working of the miracle itself, takes place "off camera" (as, in Chapter 1, does the similarly pivotal event of Jesus' baptism by John). We are left to speculate as to how it was done. My assumption would be that, since Jesus now fully embodies the creative Word, the water was transformed into wine through that Word, in the same way that the primordial chaos was transformed into a cosmos -- that is, through the power of Primary Thinking. If the miracle was accomplished by thought alone, without any of the usual shuffle-duffle-muzzle-muff one associates with a magical "working," that could explain why the act itself is not described: there simply was no observable act. All the observers could see was that there had been water, and then somewhere along the line it had become wine instead.

It may seem too obvious a question to ask, but why and how was Jesus able to do this, and what is the significance of this ability? Obviously, ordinary people lack the ability to transform water into wine simply by willing it to be so. John, like the other Gospel writers, places great emphasis on Jesus' paranormal powers and presents them as a legitimate reason for believing in him and his message.

One very common view is that human beings as such do not and never can have the powers Jesus exhibited, that they properly belong to angels and to God himself, both of which are thought of as being fundamentally different from man. Any miracle apparently performed by a human being is actually performed by a superhuman being (God or an angel) and is evidence of that the human wonder-worker is in communion with that being and receives its support and authorization. Since (for reasons that are not clear to me) superhuman beings are assumed to be sharply divided into Good and Evil camps, with none of the shades-of-gray we find among humans, a human who exhibits "miraculous" powers must be in league with the one camp or the other -- must be, that is, either a saint or a witch.

I don't think this line of reasoning is applicable to Jesus as described in the Fourth Gospel. His miracles are not performed for him by superhuman beings as a sign that he enjoys their favor; rather, they are performed by a human being: Jesus himself. He is a man who has come to embody the creative Word -- who has become divine -- and the powers he manifests are human powers -- fully realized in Jesus, but potentially available to human beings as such. When William W. Phelps wrote that Jesus came to earth "to walk upon his footstool and be like man, almost," he was missing the point: Jesus was a man; a man may be God; to be human is to be potentially divine.

The question, then, is in what this divinity consists. What was it about Jesus that made him so different from an ordinary human being that he was able to work miracles? If he was actually a superhuman being disguised as a man, that would be an easy way of explaining the difference, but John does not leave that option open to us. Nor can we imagine that his powers were a matter of technology or of techniques mastered through long practice, as if Jesus were a particularly advanced yogi. The difference must be something altogether simpler and deeper.

So far, the closest this Gospel has come to explaining what made Jesus the Son of God is the brief description of how others may become sons of God: "But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name: Which were born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God" (John 1:12-13). This idea of being "born" again in some metaphorical sense will be a major theme of Chapter 3, and I will defer a fuller discussion to my notes on that chapter. At this point, I just want to emphasize that miracle stories show Jesus to be very different from ordinary men and invite us to try to understand how and why.

*

In the previous chapter, the author has just been contrasting Moses and Jesus, and perhaps this story is a continuation of that. Moses' first miracle was turning the water of the Nile into blood. The Exodus account even mentions that there was "blood throughout all the land of Egypt, both in vessels of wood, and in vessels of stone" and that "the river stank, and the Egyptians could not drink of the water of the river" (Exodus 7:19, 21). Wine is superficially similar to blood ("the blood of grapes," Genesis 49:11), but the two miracles are opposites in terms of their effects, one being a curse and the other a blessing.

*

The governor of the feast assumes that the bridegroom is the one responsible for providing wine, choosing which wine to serve first, and so on (though I would have thought it would be the governor's own responsibility; in what does the "governing" of the feast consist if not in dealing with such things?). In fact, Jesus has dealt with that. The early Mormon apostle Orson Hyde considered this proof that Jesus is himself the bridegroom at this wedding, but I don't find this a very defensible reading. If Jesus were the bridegroom, and as such responsible for providing wine, why would he say "What concern is that of ours?" when informed that the guests have no wine? And why would the servants have to be told by his mother to follow his instructions? In fact, it seems plausible that "mine hour is not yet come" means simply, "I'm not the one getting married here; my time to host a wedding feast will come later."

Assuming then, that Jesus is not the bridegroom, we can only imagine how the bridegroom reacted to this confusing information about the wine he was supposedly providing -- or what happened when he finally discovered that his servants had been ladling wine out of wash basins. If, as I assume, these basins were situated just outside the entrance to the feast venue, the guests probably would have seen them again on their way out and realized where their wine had come from -- a pretty embarrassing situation for the bridegroom! There's probably a very interesting untold story here.

*

[11] This beginning of miracles did Jesus in Cana of Galilee, and manifested forth his glory; and his disciples believed on him.

"Signs" would be a more strictly accurate translation than "miracles." The emphasis is not on that fact that this is an extremely unusual sort of occurrence, contrary to the commonly observed course of nature, but rather that it is an indication of Jesus' identity and nature.

I was a bit surprised to discover that the word translated "glory" is δόξα -- a word which even someone with little Greek might recognize as a key term in Platonic philosophy: one generally translated as opinion, as contrasted with knowledge (ἐπιστήμη). It is an etymological component of such words as orthodox ("having right opinions") and paradox ("what is contrary to common opinion"). How do we get from that to "glory"? Thayer identifies three primary senses of word as used in the New Testament; I quote here only the basic definitions, omitting his very extensive notes and references.

I. opinion, judgment, view: in this sense very often in secular writ; but in the Bible only in 4 Macc 5:17

II. opinion, estimate, whether good or bad, concerning some one; but (like the Latin existimatio) in secular writings generally, in the sacred writings always, good opinion concerning one, and as resulting from that, praise, honor, glory

III. As a translation of the Hebrew כָּבוד, in a use foreign to Greek writing, splendor, brightness

How are we to interpret the word in this passage? Thayer says that the first sense does not occur in the New Testament, but I am not prepared to take his word for that or to assume that all NT writers used the Greek language in the same anomalous way. It is certainly true that the miracle is, among other things, an expression of Jesus' opinions or views. For example, it shows a positive, or at least a tolerant, view of the use of alcohol (Jesus was not an ascetic like John the Baptist), as well as a complete disregard for rules and what-is-done.

In the second sense, "his glory" would mean "the esteem in which he is held by others" -- and while a miracle could obviously elicit such esteem, it seems strange to describe it as manifesting it. I suppose the episode does indicate the high esteem in which he is held by his own mother (seen in her confident assumption that he would be able to conjure up some wine). If the miracle is accomplished by giving a command which is literally obeyed by the elements, it would also show that he is held in high esteem by the elemental intelligences. Or perhaps we are to assume a slight semantic shift, and understand that what he manifested his worthiness to be held in high esteem -- his greatness -- rather than that esteem itself.

As for the third sense, as bizarre as it might seem to someone whose exposure to Greek has been primarily non-biblical, δόξα is undeniably used in the NT (and, apparently, the Septuagint) in the sense of "brightness." When the angels appear to the shepherds in Luke's Christmas story, we are told that "the δόξα of the Lord shone round about them" (Luke 2:9). In the present context, this sense could be used only metaphorically, meaning something like "greatness" or "majesty."

*

Who believed in Jesus based on this miracle? Only those who were already his disciples. As discussed above, the circumstances of this particular miracle were not conducive to winning over the wedding guests.

*

[12] After this he went down to Capernaum, he, and his mother, and his brethren, and his disciples: and they continued there not many days.

Nothing is said about why they went to Capernaum (on the Sea of Galilee, not far from Nazareth or Cana) or what they did there. Since his mother and brothers accompanied him we might infer that they were paying a visit to relatives.

*

The cleansing of the Temple

[13] And the Jews' passover was at hand, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem.

"The Jews' passover" is redundant in English, but not in Greek, where the same word (πάσχα) can refer either to the Jewish feast of Passover or to the Christian feast of Easter. We can infer that the observance of Easter was already well established by the time this Gospel was written.

*

[14] And found in the temple those that sold oxen and sheep and doves, and the changers of money sitting: [15] And when he had made a scourge of small cords, he drove them all out of the temple, and the sheep, and the oxen; and poured out the changers' money, and overthrew the tables; [16] And said unto them that sold doves, Take these things hence; make not my Father's house an house of merchandise.

In the Synoptics, Jesus is dead within a week of this outrage. In John, it occurs at the beginning of his ministry and he appears to suffer no consequences. John's version is, at least at first glance, less believable. (I do not take seriously the inerrantist assumption that the Synoptics and John are describing two different events, that Jesus cleansed the Temple twice.)

What exactly is Jesus objecting to? People came to the Jerusalem Temple from all over the Jewish world to offer animal sacrifice, so it seems reasonable that the Temple should offer animals for the purpose, and that people should pay for them. (Offering free livestock to worshipers, besides likely being economically impracticable, would destroy the ritual slaughter's character as a sacrifice.) Most of the animals would have been bought by travelers from abroad (since locals could just bring their own), so offering currency exchange services also seems reasonable and necessary. The Synoptic version of this episode has Jesus accuse the merchants and money-changers of turning the Temple into a "den of thieves" -- implying that they were charging dishonest prices or otherwise cheating their customers -- but there is no hint of this in John.

The most conservative reading would be that Jesus' only objection was to where these business transactions were taking place. People should buy their shekels and their livestock elsewhere in Jerusalem, not in the Temple complex itself. His concern was with maintaining the distinction between sacred and profane spaces, hence his injunction to "take these things hence" and sell them somewhere else. Against this interpretation, there is the episode at Jacob's well in Chapter 4, where Jesus seems to de-emphasize the importance of the Temple as a place of worship.

More radically, he may have been objecting to the whole idea that religious worship should have anything to do with commerce, that the activities in the Temple should be a source of income for anyone. As I have said above, I do not consider this a reasonable objection. Any religion that revolves around animal sacrifice is inevitably going to have its economic aspect.

Which brings us to the most radical possibility of all -- that what Jesus objected to was the whole system of worship by animal sacrifice, precisely because it was economic in nature and thus tended to turn God's house into a house of merchandise. This may seem extreme, but it was not without precedent; prophets and priests seem often to have been at odds, and it is not hard to find in the Old Testament prophetic polemics against the Temple cult. I do not believe there is any reference in the Gospels to Jesus directly participating in or condoning an animal sacrifice. Even when he supposedly keeps the Passover with his disciples (the Last Supper), the only things on the menu appear to be bread and wine. Pope Benedict XVI had the following to say about Christ's apparently lamb-less Passover.

In the evangelists' accounts of [the Last Supper] there seems to be a contradiction between the version as told by John and those of Mathew, Mark and Luke. According to John, Christ died on the cross at the exact moment when in the temples nearby, the lambs were being slaughtered for the Paschal feast. His death coincides with the sacrifice of the lambs. That however means that he died on the eve of Passover and therefore could not personally celebrate the Paschal feast – this at least is what seems to be. According to the other three evangelists Our Lord's last supper was a traditional Paschal feast into which he inserted the novelty of the gift of His body and blood. Until very recently this contradiction seemed irresolvable. Most of the exegetes were of the opinion that John did not want to give us the exact, historic date of Christ's death, but had instead chosen a symbolic date to highlight the one profound truth: Jesus is the true Lamb of God who shed his blood for us.

In the meantime the discovery of the Qumran writings has led us to a possible and convincing solution that, while not accepted by all, possesses a great degree of probability. We are now able to say that John's account of the passion is historically precise. Christ really did shed his blood on the eve of the Passover at the hour of the slaughter of the lambs. However he celebrated Passover with his disciples according to the Qumran calendar, therefore at least one day earlier -- he celebrated it without the lamb, as according to the traditions of the Qumran community, which did not recognize Herod's temple and was waiting for a new temple. Christ therefore celebrated Passover without the lamb -- no, not without the lamb: in place of the lamb he gifted his body and blood. (source)

According to Benedict, Jesus celebrated Passover without a lamb because the lambs had to be slaughtered in the Temple, and he did not recognize Herod's Temple as a true temple -- which is hardly consistent with his calling Herod's Temple "my Father's house" in the passage now under discussion. While Benedict's explanation of why there was no lamb thus leaves something to be desired, his recognition that there was no lamb is significant. There are, it seems, very good reasons for believing that Jesus never once participated in the priestly cult of animal sacrifice, not even at Passover.

Certainly animal sacrifice has never been a feature of Christian worship. The standard explanation for this is that Jesus was the great and last sacrifice, making further animal sacrifice unnecessary. But from a Christian point of view, animal sacrifice never was necessary, never had the power to save, never was anything but a symbolic anticipation of the Passion, and there's no obvious reason why it could not have continued after Christ as a commemoration of his sacrifice, playing the same role that Communion has in fact played in historical Christianity. Is it possible that the real reason for the cessation of animal sacrifice was that Jesus was against it from the beginning, even before his Passion?

This is not to suggest that Jesus was a vegetarian or was opposed to the slaughter of animals. We are told that he ate fish at least, and there is no reason to suppose he ate anything other than a normal diet for the culture in which he lived. In his cleansing of the Temple he never said anything like, "Make not my Father's house an house of bloodshed." His objection was apparently to the economic aspect of the Temple cult, and its way of introducing Mammon into the house of God.

*

I wonder if there is any significance to the fact that he apparently treated the dove-sellers differently from the others. He drove away the sheep and oxen and overthrew the tables of the money-changers, but to the dove-sellers he did no violence but only spoke: "Take these things hence; make not my Father's house an house of merchandise." Could this possibly have anything to do with the recent appearance of the dove as the sign of the Spirit of God? I suspect that, in Greek as in English, "make not my Father's house an house of merchandise" is ambiguous as to which is the object and which the object complement, allowing for this reading: "Take these doves, which represent the Spirit, somewhere else. This building is obviously a house of merchandise now; don't try to make it a house of God." Not a very likely reading, all things considered, but intriguing enough that I thought it worth noting.

*

[17] And his disciples remembered that it was written, The zeal of thine house hath eaten me up.

The reference is to Psalm 69.

[7] Because for thy sake I have borne reproach;

shame hath covered my face.

[8] I am become a stranger unto my brethren,

and an alien unto my mother's children.

[9] For the zeal of thine house hath eaten me up;

and the reproaches of them that reproached thee are fallen upon me.

The disciples apparently read this prophetically, with David (the "I" of the psalm) speaking in the voice of the future Messiah. If "thine house" means the Temple, it would make sense to read it as a prophecy, since David himself lived and died before the Temple was built. (I suppose it could be read as a reference to David's unrealized desire to build a temple, as described in 2 Samuel 7.)

Given the immediate context, in which the Psalmist describes being alienated from his biological family, I think there is a strong case for reading house in the sense of family or household. In essence, the Psalm is saying, "I have become a stranger to my own family. God is my family now, and who insults God, insults me."

Of course this and the Temple reading are not mutually exclusive, and Jesus' reaction to commerce in the Temple seems to encompass both: "Make not my Father's house an house of merchandise." He took a perceived desecration of God's Temple personally because he saw God as family.

Again we are faced with the question of how to understand these "fulfilled prophecies." I find it very hard to believe that David foresaw Jesus' cleansing of the Temple and wrote a conscious prophecy of it into his psalm. Possibly he subconsciously "picked something up" as he was writing about his own feelings; more likely, Jesus "fulfilled" the psalm in a more general way: the Messiah was supposed to be a second David, and Jesus, by expressing the feelings expressed in the Psalms, was showing himself to be a man after David's own heart.

*

[18] Then answered the Jews and said unto him, What sign shewest thou unto us, seeing that thou doest these things?

I find it surprising that the immediate reaction of "the Jews" was not to have Jesus arrested but to ask for a sign. Certainly his actions in the Temple constituted a moderately serious property crime and could have been punished as such.

There is in the Old Testament a tradition of what might be called "prophetic theater," where the prophet underscores his message by performing symbolic actions, some of them quite unusual and involved. Granted that was long time before Jesus' time, and granted many of the prophets involved got stoned, sawn in half, or cast into miry dungeons for their labors -- but perhaps the Jews were tentatively willing to countenance Jesus' actions in the Temple as prophetic theater, provided he could prove he was a legitimate prophet by giving a sign that he enjoyed God's favor. If the Jews were not thinking along these lines, I find it difficult to make sense of their reaction.

*[19] Jesus answered and said unto them, Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up. [20] Then said the Jews, Forty and six years was this temple in building, and wilt thou rear it up in three days? [21] But he spake of the temple of his body. [22] When therefore he was risen from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this unto them; and they believed the scripture, and the word which Jesus had said.

According to Josephus, construction on Herod's Temple commenced in 22 BC and continued until it was destroyed in AD 70. The 46-year figure suggests that this episode took place around AD 24, a bit earlier than commonly accepted dates for Christ's ministry.

This is a sarcastic non-answer to the request for a sign. Obviously his listeners were not prepared to put him to the test by destroying the Temple or (if we grant that "he spake of the temple of his body") by murdering him. Jesus has just turned water into wine in Cana as a "beginning of signs," and we are told that "when he was in Jerusalem at the passover, in the feast day, many believed in his name, when they saw the miracles which he did" (v. 23), so why did he refuse to perform a miracle in this case? And what did he hope to communicate by proposing the particular sign that he did?

John's interpretation is that "this temple" meant Jesus' body, and that he was announcing -- some two years before the event -- his intention to rise from the dead on the "third" (meaning the second) day following his execution. No one interpreted his statement in this way until after his resurrection, nor could they possibly have been expected to do so. Sometimes Jesus' listeners seem to be obtusely literal-minded in their understanding of what he says, but in this case their interpretation seems perfectly natural. If you say "this temple" while standing in an actual temple, any normal person is going to assume that you are making some reference, whether literal or metaphorical, to the building in which you are standing -- not to your own body.

I'm willing to accept that Jesus was leaving "Easter eggs" (so to speak) for his disciples to discover after the fact, but not that that's all he was doing -- not that he spoke without the slightest intention of communicating anything understandable to the people to whom he was speaking. If Jesus was a charitable person, we must assume that the Easter-egg value of his words was secondary and that his reply to his questioners was a good-faith attempt to communicate something which, with a little thought and sincerity, they could reasonably be expected to understand.

Could he have meant "Abandon your priests-and-rabbis religion of ritual and law, and I will make you a new religion"? Probably not. Elsewhere in this and the other Gospels, Jesus stresses the continuity of his message with Judaism -- he is the promised Messiah, Moses wrote of him, he came not to destroy the law but to fulfill it. Besides, "in three days I will raise it up" implies restoring the original edifice, not replacing it with something new. (Mark 14:58 does have someone say of Jesus, "We heard him say, I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and within three days I will build another made without hands" -- but the statement is attributed to a "false witness.") Perhaps, alternatively, he meant "Corrupt and destroy your ancestral religion as much as you will, but I will purify it and restore it."

More likely, I think, Jesus' completely unreasonable demand that they destroy the Temple was meant simply to convey that he considered their demand for a sign equally unreasonable. As discussed in my notes on John 1, the kingdom of God cometh not with observation. No conceivable empirical evidence could be sufficient to establish that Jesus is divine, so the insistence on a sign is misguided. Perhaps Jesus' reply was meant to trigger the following imagined dialogue in his listeners' minds.

Jesus: If you want a sign, destroy this Temple, and in three days I will raise it up again.

Skeptic: Raise up in three days what it took 46 years to build? That's impossible!

Jesus: Precisely. Doing something impossible would constitute a miraculous sign, would it not?

Skeptic: But how could we dare destroy the Temple of God?

Jesus: Don't worry. If I am who I say I am, I have both the authority to make the request and the power to bring the Temple back after you destroy it. You will not have displeased God, and you will still have your Temple.

Skeptic: But we do not know whether you are who you say you are. That is what the sign is supposed to establish. And suppose we destroyed God's own Temple only to find that you had lied to us! The Temple would be in ruins, and we would be guilty of a terrible sacrilege.

Jesus: Yes, there's always that risk.

Skeptic: The risk is unacceptable. We decline to destroy the Temple, and we reject your message.

Jesus: And why do you consider that the safer course of action?

Skeptic: Because we do not know who you are or what authority or power you may have, but we do know that the Temple of God is holy.

Jesus: Because its holiness has been proved to you by a miraculous sign?

I do think that the response "Forty and six years was this temple in building, and wilt thou rear it up in three days?" shows the insincerity of Jesus' questioners. They ask him to do something miraculous (i.e., seemingly impossible) and then object that the feat he proposes is impossible.

*

[23] Now when he was in Jerusalem at the passover, in the feast day, many believed in his name, when they saw the miracles which he did. [24] But Jesus did not commit himself unto them, because he knew all men, [25] And needed not that any should testify of man: for he knew what was in man.

We are not told what specific miracles he did in Jerusalem. The seven miracles that are described in full in this Gospel were apparently chosen for a reason, because the author considered them especially significant. He is not simply relating every miracle he has seen or heard about.

Just after that discussion of why miraculous signs could never really prove Jesus' divinity, we read that many people did in fact believe in Jesus based on his miracles -- but Jesus seems not to have had a very high opinion of such belief. The word commit is better translated as entrust and is the same Greek word translated as believed in v. 23. Essentially, many people believed in Jesus, but for his part he didn't believe in them at all. He did not accept these people as his disciples, because their belief was built on sand.